Every refugee, every asylum seeker, in Europe and all over the world, brings with him his own story. A story that is always different, a story that is always painful, like every forced departure from home.

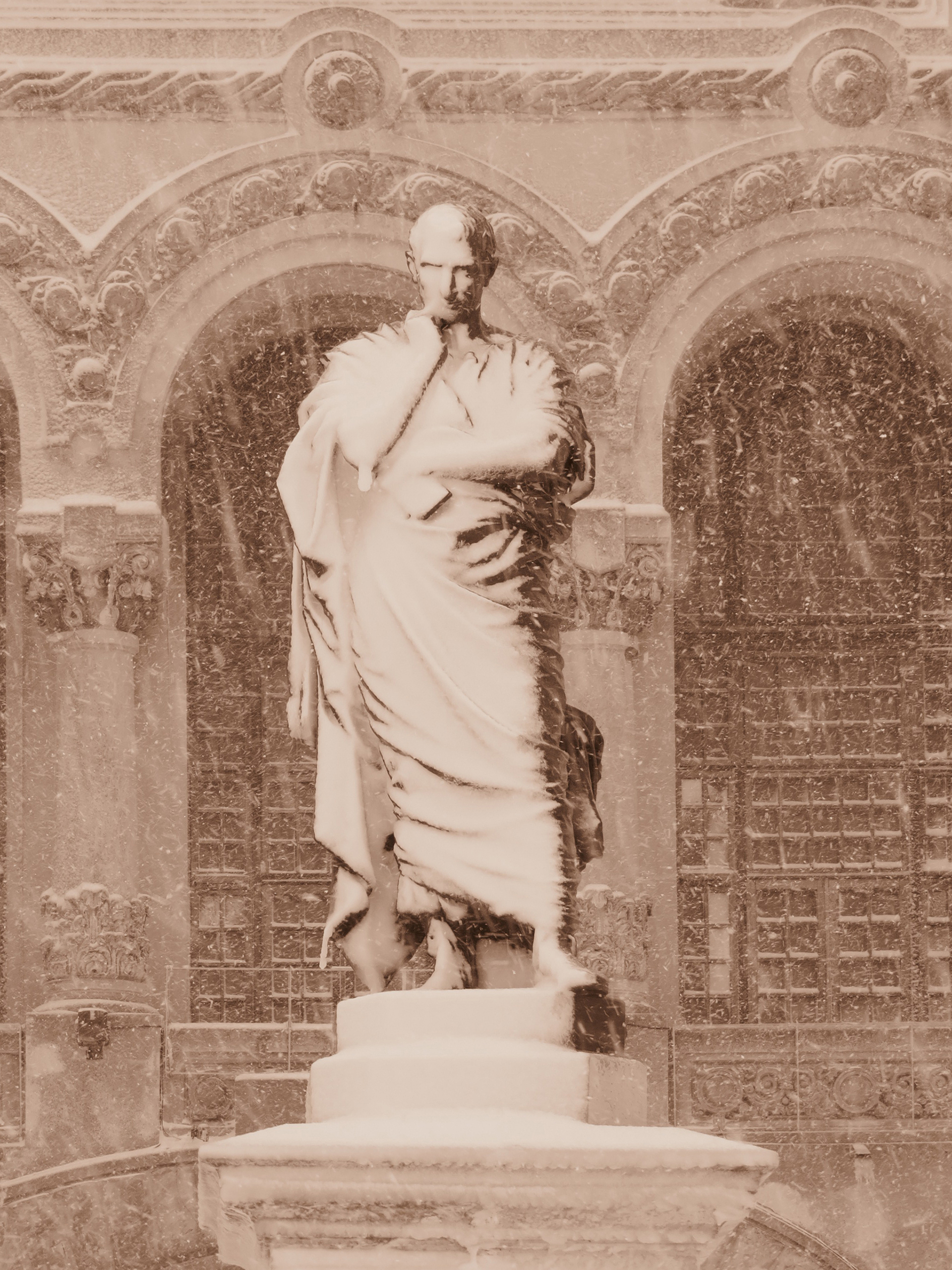

Exile, today as a thousand years ago, is a scar. In Constanta, on the Black Sea, there is a statue of a great Roman poet, Publius Ovidio Nasone. How did this statue come to be so far from Rome?

Ovid was exiled 2000 years ago by the Roman emperor Augusto to the town of Tomis, today’s Constanta, where he died without ever seeing his distant homeland again.

Even today, his story is still debated in relation to the process of exile, which in ancient Rome was called relegatio. Neither the reasons for the exile nor its concrete legal effectiveness are clear.

According to some sources, Ovidio paid for the libertarian tone of his poems, which struck at the heart of the social principles on which Augusto wanted to build his government.

Ovid’s poems speak freely about love, the role of women in society, the relationship between men and women and religion. Augusto, in whose figure political and religious power coincided, felt threatened by the poet’s enormous popularity, especially among the youth of Rome 2000 years ago.

At that point, cornered, the poet left Rome and retired to the Black Sea. His poems of exile hint at the reasons for his exile, without ever fully explaining them, but what one perceives is the pain and the lack for the distant homeland.

Today, Constanta has dedicated a statue to Ovidio, while all over the world his art is immortal. But Ovidio, like his statue, tells a story that is as painful today as it was then: that of the exiles.

Just imagine how easy it is, looking at the statue of Ovidio in Constanta, to think of all those who every day flee from war in Libya, Syria, Afghanistan and elsewhere.

How many of them are artists who, perhaps in situations of violence due to conflict or because of censorship in regimes without freedom, are denied the chance to express themselves freely? How many of them, like Ovidio, pay the price for having the courage to speak freely, even if this entails the danger of going against the powers that be?

Every time a person fleeing arrives in Europe or elsewhere, asking for protection, we do not know what persecution he or she has escaped from, we do not know what burden he or she is carrying. For this reason and for many others, everyone must be given the opportunity to tell their story and to be helped.

The statue of Ovidio is a place to reflect, on the borders of Europe and on borders in general. His painful words on the condition of exile, celebrated today as those of a great poet, were yesterday the unheard words of a man who was disliked by the powers that be.

That statue reminds us that many leave their homes because they are forced to, because they have no alternative. And that even when they manage to save themselves, they keep that scar, that of exile, to which the scar of rejection and hatred should not be added.

by Christian Elia